New York via Glasgow

Posted by Pete on 25th Apr 2022

Our historian, Pete, tells the story of his family's journey from Tsarist Lithuania to the banks of the River Clyde

Long ago, before the rise of commercial aviation, the ocean voyage from Lithuania to the United States went via Scotland.

Around the turn of the 20th century, several thousands of people made this long journey, my ancestors among them – Jewish refugees fleeing the Tsarist pogroms which began in the late 19th century.

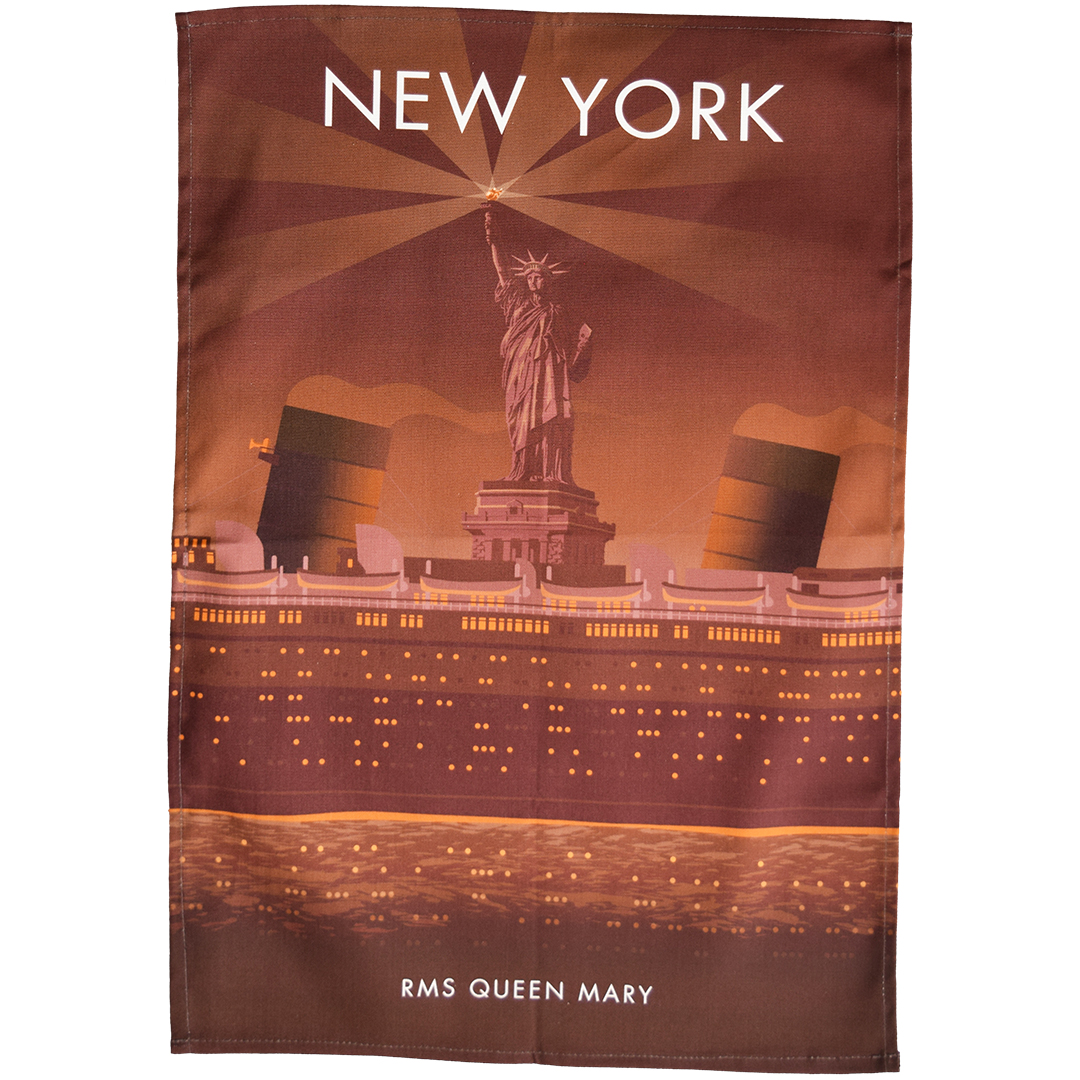

Many set their hearts on New York City, a beacon of hope shining across the Atlantic.

Scotland, meanwhile, was only meant to be a waystation – the first step on this long voyage.

New York's Statue of Liberty symbolised for many a land of welcome and new beginnings

Click here to view our New York tea towel

But in many cases, Scotland became the unexpected endpoint of their journeys – and it was in the port city of Glasgow that my own ancestors settled.

Maybe there wasn’t enough money left for the transatlantic leg of the journey – most Jewish emigrants from the western reaches of the Russian Empire were impoverished workers, after all. Or perhaps Scotland presented opportunities not worth passing up.

Whatever the reason, the exodus from the Russian Empire at the turn of the century became the founding moment of large-scale Jewish communities not just in Glasgow but across the British Isles.

Out of necessity, the Jewish newcomers gravitated to areas where housing was cheap and living conditions rough. In Glasgow, this was the slumland of the Gorbals, south of the Clyde.

They were looking for work, and so survival, in this rapidly industrialising city.

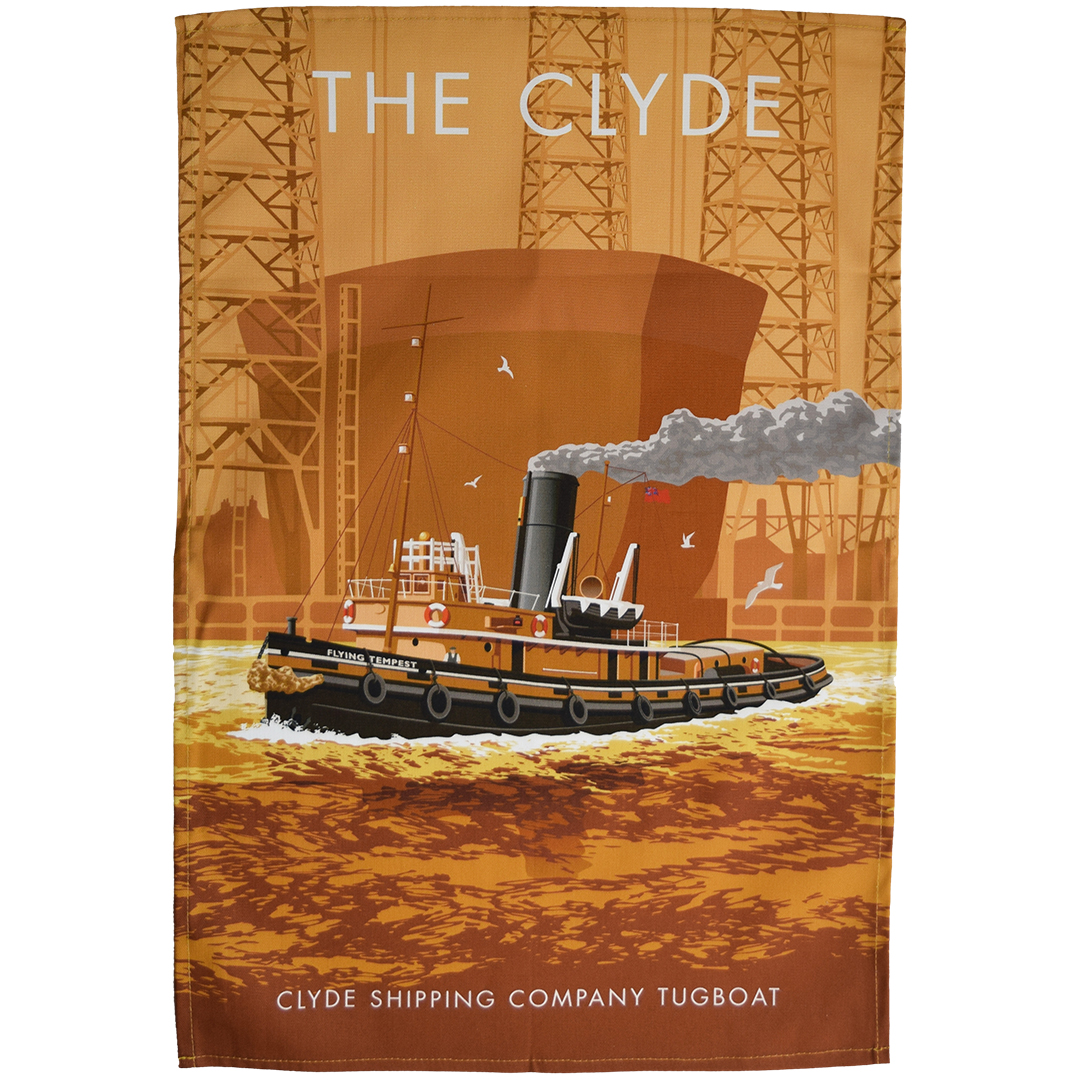

The second longest river in Scotland, the Clyde runs through the heart of Glasgow and was vital to the city's industrial history

Click here to view our Clyde tea towel

But as well as building ships and cleaning streets, this influx of Europeans built and developed a thriving cultural life amid the grim smoke of Edwardian Glasgow.

My family, for instance, lived only a few doors down from the South Portland Street Synagogue, built in 1901 in the heart of the Gorbals.

This image of Scotland may seem quite different from the stereotypes we’re used to.

Rather than tartan kilts and Highland cattle, 20th century Glasgow tells a whole other story: a bustling, noisy and culturally kaleidoscopic city, woven from threads reaching far and wide across the world.

But who says it has to be either/or? In fact, these two Scotlands – rural and urban, old and new – were, and still are, inseparable.

The Highland Cow is one of the classic symbols of rural Scotland

Click here to view our Highland Cow tea towel

My great great grandad, on arriving in Glasgow from Lithuania, worked as a pedlar, travelling across the Scottish countryside hawking his wares. He may have lived in Glasgow, but it was the rural highlands and lowlands that gave him his livelihood.

One of his sons, Michael Sachs, was killed at the Battle of Loos in 1915 while serving in the Highland Light Infantry during the Great War.

Nor was he alone: over a thousand Jewish Glaswegians served in the First World War, and 80 of them besides Michael lost their lives.

Their families had only arrived in Scotland a handful of years earlier, but they still went to the trenches to fight and wore the ancient tartan of the Highland Infantry.

Now I don’t know about you, but I think that says a lot.

My family has since moved south of the border – my grandpa, Mike, was the last of us to be born in Glasgow.

But Scotland keeps a special place in my soul and identity. For us, it offered sanctuary in dark times – a place where life and hope could begin again.

And of course, no tribute to Glasgow would be complete without a celebration of Glaswegian wit - captured brilliantly in our Coneheid tea towel.

Included in Lonely Planet's 'top 10 most bizarre monuments on earth', Glasgow's Coneheid statue is one of the city's many iconic landmarks

Click here to view our Glasgow Coneheid tea towel

The Duke of Wellington's statue has stood in Royal Exchange Square for over 170 years - my Glaswegian ancestors would probably have known it well.

The orange traffic cone, however, is a newer feature.

Since it first appeared in the 1980s, the bright orange traffic cone on the statue's head has become a symbol of Glasgow's humour: cheeky, rebellious, and unique, like the city itself.

All in all, I reckon my ancestors would've found it pretty funny. I certainly do!